Timothy Wong

just a person passionate about sustainable economic development.

just a person passionate about sustainable economic development.

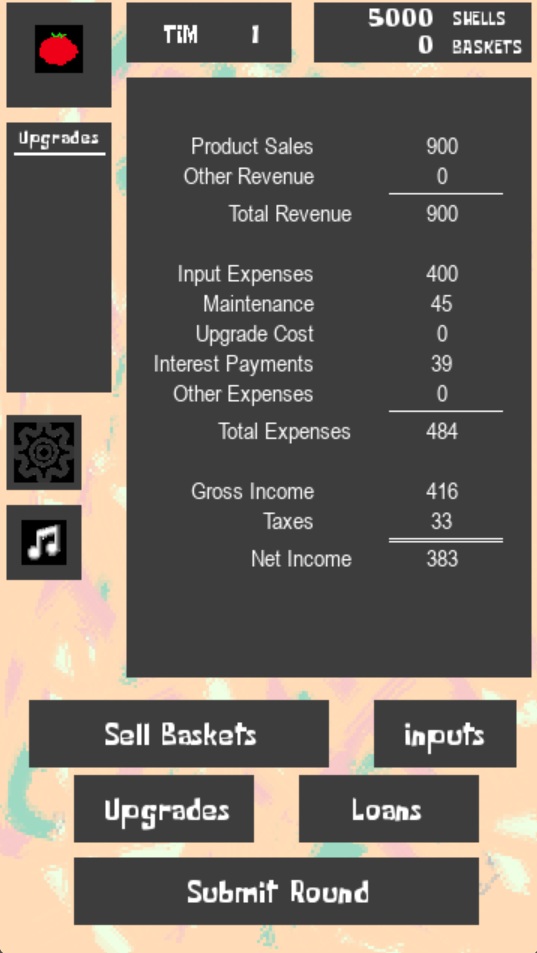

Capital Cultivations is an app-based educational game I am developing in Python. Its primary objective is to provide educators in lower-income contexts with a fun and accessible way to begin teaching finance and risk navigation. Using a turn-based system, players simulate owning a farm. They will need to understand how factors such as product selection, loan availability, and physical capital can affect the success or failure of their ventures. The game will offer both single-player and multiplayer options, allowing players to experiment with different strategies, both individually and in comparison with their peers.

My main interests include topics related to international relations, education, and sustainable economic development. Most recently, I finished a fellowship in public policy under Dr. Ram Fishman. Our work involved using software such as Stata, LaTeX, and Qualtrics to evaluate educational policy for migrant interns in Israel. Additionally, I have experience in tourism, tutoring, and ski resort operations.

My resume is available for download directly below. Please also feel free to reach out with any inquiries using the links at the bottom of the website. I hold a Bachelor's degree in Physics and History from Gettysburg College, a Master's degree in International Affairs from Johns Hopkins University, and a Master's degree in Sustainable Development from Tel Aviv University.

Related Material: Timothy Wong's Public Policy Thesis PDF

When I first built this website, I wanted a space to reflectively log ideas related to my burgeoning career at the intersections of international relations, development economics, education, public policy, and sustainability. It took a lot of effort to pivot away from my previous career paths in physics, tutoring, or tourism. There's still a lot left for me to do, like getting a job 😅😅😅😅.

This writing process is hopefully about defining who I am, what I'm passionate about, and what my career objectives are. Although I try to stay busy with intermediate projects such as app development, the future remains unclear to me.

Logically, it makes sense to start off by talking about my greatest personal academic achievement so far: my master’s thesis evaluating migrant intern policy in Israel. It's not a project I envisioned when I first started studying international affairs at Johns Hopkins, but it is a project that I felt encapsulated who I am most as a student of sustainable economic development. It has adventures working in the field, creative empirical methodology, and a touch of politics. Most importantly, it centered around understanding and navigating human nature.

If desired, the paper is available for reading using the link above. In short, I investigated two possible causal factors of intern career intentions: their familial traditions and their farm assignments in Israel. The idea first came to me when I visited Ein Yahav, a farming community in the Negev Desert. They produced a wide variety of products, such as dairy, aquaculture, fruits, and vegetables. With that variation in productivity came a variation in job descriptions for the interns. How would a student who was "unfortunately" assigned to work in a boring packaging factory approach their career compared to one who was "fortunately" assigned to an interesting and lucrative mushroom farm?

Using a series of OLS regressions, I found significant evidence that a student's career intentions are indeed influenced by these instances of luck. Thus, a possible improvement to the program may be the development of a more equitable system of intern distribution. Furthermore, intern education could benefit from further developing the curriculum to specifically augment students' family farming traditions.

I want to highlight three personally rewarding aspects of this investigative endeavor. First, my advisor had so much trust in my abilities that I essentially ran the entire operation from start to finish. I built the survey, collected the data, designed the empirical procedure, and wrote the code. Secondly, this was an observational study done in the field, which meant I was privileged to directly interact with both students and teachers across Israel. Finally, I feel the analysis I uniquely designed could not have been done without a strong understanding of the statistical mechanics operating under the hood. I have yet to find another paper that used regressions in the manner I did.

Deaton, Angus. 2010. "Instruments, Randomization, and Learning about Development." Journal of Economic Literature, 48 (2): 424–55.

Mosteller F. The Tennessee study of class size in the early school grades. Future Child. 1995 Summer-Fall;5(2):113-27. PMID: 8528684.

I think that one aspect that I enjoy about social sciences is the application of empirical processes to learn more about the messy human element. In undergraduate, I used to work in an optics laboratory. My job involved shining a blinking laser unto a blinking lightbulb and then measuring that blinking lightbulb. It actually was interesting because it was an exploration of synchronization phenomenon. Anyway, as one can imagine with any physics experiment, the conditions were sterile and all variables were controlled but one.

Fast forward a couple of years, and I was assigned to present the usage of RCTs in my econometrics class. Randomized control trials have become more and more popular in recent times, probably thanks to the amazing work of Banerjee and Duflo. Their work using experimentation brought the fight against poverty to the front of popular culture for a time.

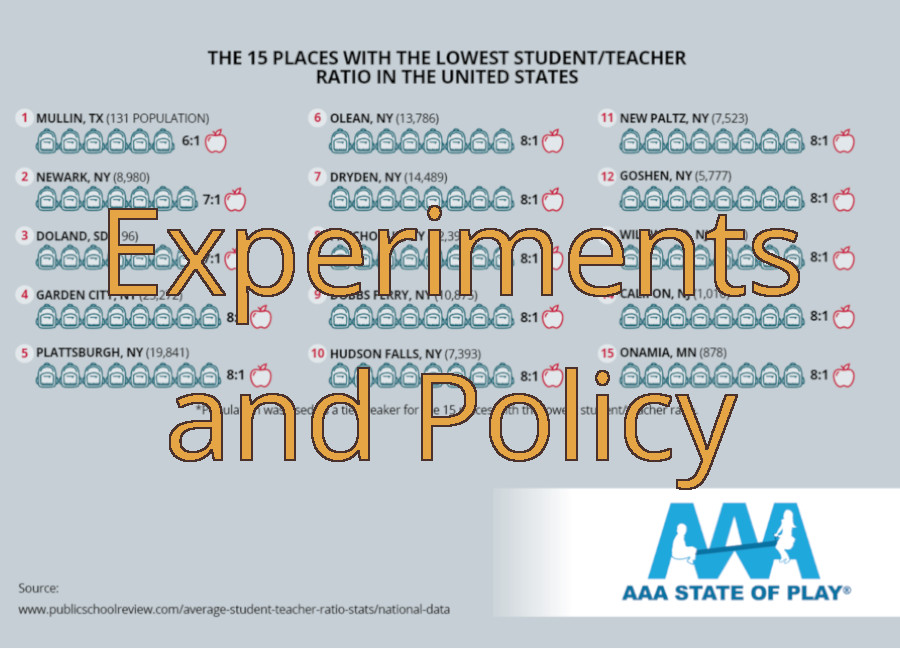

Interestingly though, RCTs actually aren't that new to the social sciences. In 1985, the Tennessee School District conducted an experiment wherein schools would split their elementary student body into two groups. One group got smaller class sizes. The other didn't. After the experiment, students from the smaller class sizes scored measurably better on standardized exams. STAR or Student Teacher Achievement Ratio was a complete success!

Then California came along and ruined it. Its school districts enacted a statewide classroom reduction scheme, spending like billions of dollars in the process. And scores just wouldn't go up very much. Nowadays it seems like academics treat the STAR experiment as a cautionary tale more than anything else, citing internal and external validity issues. Experiments done now are much better and more rigorous supposedly.

That being said. There is still one more point I'd like to echo that still applies to experimentation in policy today. Professor Angus Deaton was very vocal on his concern that experimentation in economics may become the gold standard; policy makers may begin only accepting and funding experiments because they're "more real" and "sexy" than observational studies or theory, potential pitfalls in experimentation be damned. There are merits to his points. I know right. How brave of me to agree with a Nobel Prize winner.

I do recall one time at Tel Aviv University, sitting at a research meeting going over potential projects when partnering with migrant training centers. It felt like everybody else, the other students and professors, started off from the question "how can we make an experiment out of this?" I found it creatively stunting if I was being honest, but what did I know? At the time I just felt honored to be asked to attend.

Now. I think I can stand up a bit more for other research processes. Maybe... After all, my own thesis was built out of the "lesser" observational study, and I am very proud of the ideas it has put forth.

Andersen, Jørgen, Johannesen, Niels and Rijkers, Bob, (2022), Elite Capture of Foreign Aid: Evidence from Offshore Bank Accounts, Journal of Political Economy, 130, issue 2, p. 388 - 425, https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:ucp:jpolec:doi:10.1086/717455.

I'd like to briefly discuss a paper I encountered in my Theories and Models of Economic Development class with Professor Mascagni. The paper examines the link between foreign aid inflows and the outflows of cash into offshore banking havens; yup. It explores the theme of corruption. It's a fascinating read and I highly recommend it to anyone interested. For me, it was one of the first rigorous "big-boy" academic papers where I felt I could begin to grasp the empirical analysis involved. That was very encouraging to me as a new econometrics student, and it meant to me that maybe I stood a chance in the field.

Essentially, the authors took cross-border bank deposits, and then they split them into haven (like the Cayman Islands) and non-haven countries(like Germany). The flows are then regressed on aid disbursements from The World Bank. Each time aid flowed into the country, banking deposits in havens would go up while banking deposits in non-havens wouldn't. The conclusion was that elites were grabbing this money given that they were the ones with access to these types of accounts. There is even a rough estimate of aid diverted, about 7.5% of it.

What also especially stands out are the pains the authors took to essentially fortify their argumentation. Almost immediately in the opening paragraphs, they're like "Yeah we anticipate our critics will say this, so we took like a bunch of steps to address potential endogeneity. Our results are still robust....bitch."

My understanding and appreciation of this paper is partially why I didn't scream at my advisor every time he asks "oh. what happens if we adjust this one itty bitty thing to check?" This portentous question is then always followed by me spending hours adjusting code and then reprinting everything out. It still sucked though.

Anyway, if I recall correctly, I think this paper caused a bit of drama at The World Bank, and people were fired/resigned at some point. Everybody was leaping on the whole 7.5% of foreign aid is stolen part. The dialectic view some came up with, however, is that 92.5% of aid is getting there. I think that's a more productive view of the situation.

Nowadays, almost everyone I meet has an opinion on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Even more personally challenging, these interactions often lead to people trying to get my own opinion. The issue is that I still struggle to formulate a definitive stance. It's not that I haven't tried.

At SAIS, I attended Professor Del Sarto's class, where we took a historical overview of the conflict's development, from the advent of Zionism to recent events. For my class presentation, I focused on the existence of the Israel Lobby. My paper cited authors ranging from John Mearsheimer to John Hagee. Despite both being "Johns," they held quite opposite stances on Israel.

After Italy, I even moved to Israel to study sustainable development. Since this was before the October 7 attacks, I had the privilege of traveling extensively. I visited the borders with Lebanon, Gaza, and Jordan, and explored the convoluted Old City of Jerusalem, where Israeli troops would forbid me from entering one alley but allow me into the next. It felt somewhat arbitrary, to be honest. Unfortunately, I did not have the opportunity to visit Gaza or the West Bank. In hindsight, this might have been a blessing, judging by the aggressive grilling I received before boarding the plane home to SF.

What I'm trying to say is that I have a decent amount of knowledge about the conflict, possibly moreso than the average person in the US. Because of this, I'm astounded at how easily blanket labels like genocide, ethnic persecution, antisemitism, colonialism, imperialism, terrorism, extremism, and other "isms" are thrown around. I've reached a point where I always try to start conversations with basic questions like, "Are all Israelis Jews?" or "Are all Jews Israeli?" This helps me tread carefully.

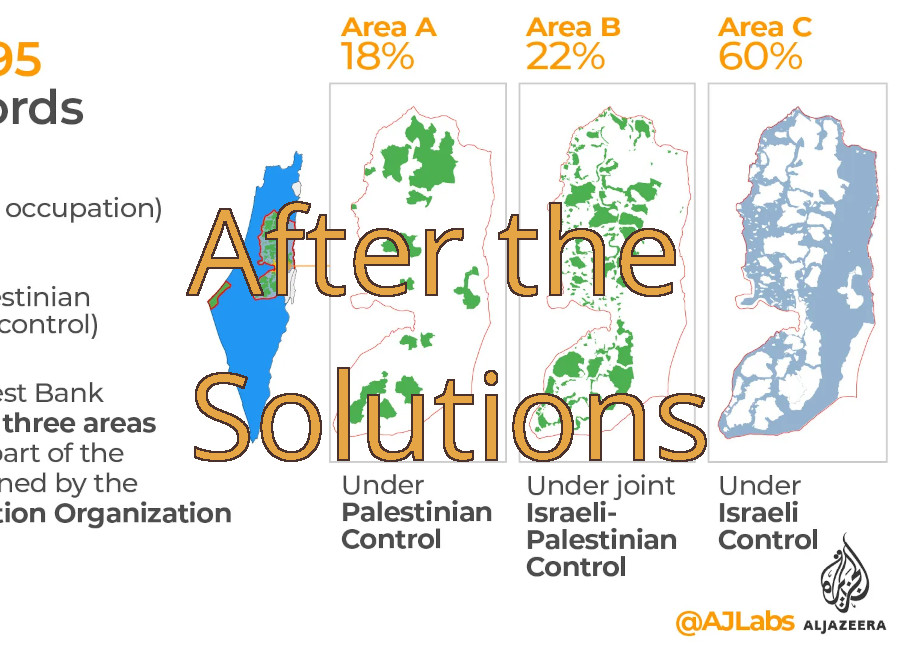

Maybe it's cowardice. Maybe it's optimism. But I prefer steering conversations toward my strength: asking what happens next socioeconomically once peace of a sort is achieved through the various one-state and two-state solutions presented. Right off the bat, I don't see how either version of the one-state solution can avoid genocide (a word I take very seriously) without heavy and difficult compromises. Palestinians aren't going anywhere, nor should they be expected to. Israelis aren't going anywhere, nor should they be expected to. Unfortunately, I doubt these combined sentiments are widely shared on either side.

Thus, the default and often lip-serviced stance is the two-state solution. But I take issue with how simply this solution is presented, not just because it likely kicks the "conflict can" down the road. The two-state solution makes little sense to me from a nation-building perspective. There are simple yet important questions that nobody seems ready to ask. How does a new theoretical Palestinian nation successfully administer two small non-contiguous territories, one of which is Swiss cheese? Will there be Palestinian roads crossing Israel? Will there be airports launching Palestinian commuter airplanes over Israel? Where will the capital be? Will there be a Palestinian central bank to issue currency to replace the widely-used Israeli shekel? How can there possibly be a growth of local institutions and not externally established parallel institutions, otherwise known as the failure of Afghanistan?

It's possible that any realistic two-state solution may not be the win Pro-Palestinian observers hope for. So what's left solution-wise? Honestly, I'm not sure there are great outcomes, just not as bad ones. I'm just a guy sitting in a café, and I just made you read a bunch of stuff for such a non-committal and pessimistic outlook on the conflict. In the end, all I can really say is that there remains a lot of work left even after the solutions to the conflict have been found. That work will require communication, cooperation, and understanding from Israelis, Palestinians, and the rest of the international community. They are all currently failing in that regard, and future generations deserve better.

Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson. 2001. "The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation." American Economic Review, 91 (5): 1369–1401.

North DC, Weingast BR. Constitutions and Commitment: The Evolution of Institutions Governing Public Choice in Seventeenth-Century England. The Journal of Economic History. 1989;49(4):803-832. doi:10.1017/S0022050700009451

Sometimes, upon asking me what I learned in school, I get family members who ask me why certain countries are more wealthy and more stable than others. Being the good SAIS student that I was, I instantly reply that certain strong institutions are the key to economic development and stability. These institutions are the rules, norms, and expectations by which a certain society chooses to operate.

Then I'd start quoting Robinson & Acemoglu and detail the statistical methodologies of how we can trace more prosperous countries to not having extractive institutions in the past. Another good one for the history lovers is to use North & Weingast to point out how the Glorious Revolution of 1688 was fundamental toward solving the credible commitment conundrum. Thus, limitations on the British Monarchy ensured higher influxes of liquidity. As one can imagine, these orations attracted rapt attention and were thoroughly convincing.

I have a new tactic now. I just tell my relatives to watch Designated Survivor. For those who have not seen it, it is a show with an amazing premise that ran for way too long. In the world of Designated Survivor, a terrorism plot decapitates the entire United States Government. Everybody is dead except for the designated survivor, the Secretary of Housing and Development. The, to me, interesting parts of the show then document how this scrappy underdog steps up and rebuilds the government.

Watching Designated Survivor allows me to reflect on the strength of certain institutions laid out in the US Legal System. Oh. All the representatives are dead? Just elect new ones! Oh no. The President is dead? No worries. It's explicitly laid out what the line of succession is, and we even an actual mechanism to always have a survivor. Oh no! The stock market is frothy? Let's just close it for a few days. Not once during the entire viewing experience did I think that the US would disintegrate into warring states of economic decay.

In fact, some of the conflicts faced by the protagonist seemed almost contrived. For example, there is no way American public would shirk the right to elect new representatives, especially in such an extreme scenario. But the show spends like a whole episode where the new president tries to rally people to even vote. After these minor conflicts, the show eventually turns into a poor man's The West Wing series near the end of the first season. That is honestly a testament to the strength of American Institutions.

But the reflections get even more interesting when compared to the Korean version of Designated Survivor, otherwise known as Designated Survivor: 60 days. It's a much tighter series, running for just a single season. The plot points are almost the same. However, even if I knew what was going to happen, the different context of Korean government structure gave it an interesting filter. I found the ending very gratifying and I finished watching the show with a sense of admiration for Korean Democracy and its institutions.

After watching the shows, I challenge people to imagine similar scenarios for other countries, a sort of thought exercise in institutional strength. Let's ask ourselves, what would happen if the entire Russian Government suddenly disappeared? My favorite personal rumination is considering what would happen if this scenario occurred in Israel.

So...poor me had to go and live in Italy for a year. And it wasn't at any cool place like Venice, Naples, or Rome. It was a place where bland ultra processed lunch meat comes from. I'm kidding! Bologna was a fantastic place, and I was super privileged to study there at SAIS. If I were to describe the city using a single word. I would say that it was comfortable. It was special living in a community that was super accepting and open while also somehow feeling very old and traditional.

While the city does definitely get a lot of tourism, I'd say it's mostly defined by its large student population. There are some fun spots though. If you're ever in town I definitely suggest hiking up to the Santuario della Madonna di San Luca. It has a great view of the city. I also definitely recommend checking out Giardini Margherita. And of course, the food of the surrounding region is amazing. Like ridiculously delicious. Like who has not heard of spaghetti alla bolognese? How about parmesan cheese?

Oddly enough, I think what makes the city most special to me was how mundane (and therefore comfortable) it could be. Like I'm thinking back now, and the two events that stick out most to my mind are getting my third COVID vaccine shot and going to the dentist. How lame is that? Also I remember going to the salumeria near my apartment and screwing up ordering mortadella because I forgot that a kilogram is bigger than a pound, like a lot bigger...

At SAIS itself, it's a tight community in and of itself. There are almost always classmates to hang out with on campus, and I found that most people are eager to do so. Apparently, it can be very different from D.C., at least according to the people who have been on both campuses. I did something different, if it wasn't blatant enough in my other entries.

So yeah. Check Bologna out if you have the chance. I do not think it would be a regretful choice.

Patankar, Neha & de Queiroz, Anderson & DeCarolis, Joseph & Bazilian, Morgan & Chattopadhyay, Deb. (2019). Building conflict uncertainty into electricity planning: A South Sudan case study. Energy for Sustainable Development. 49. 53-64. 10.1016/j.esd.2019.01.003.

Related Material: Timothy Wong's UV LEDs Paper PDF

I think for this entry I would like to write about a fun concept I came across in my Technologies for Development class at Tel Aviv: conflict hedging. As unfortunate as it sounds, poor states are often fragile states. There's probably a connection there... Anyway the nature of the job means working in non-ideal scenarios. We need to ask ourselves "what can harm this project? If a war erupts in the next few years, can this really bridge really get finished or even survive?" Stuff like that.

In my opinion, that scenario is when decentralized technologies can truly shine. A classic example is the usage of solar panels. One paper that I recommend for reading is Pantankar's Building Conflict Uncertainty into Electricity Planning. To paraphrase her, solar panels shine in value when compared to more efficient and centralized electrical setups if the possibility of armed conflict is not exogenously considered. She particularly points out how development efforts in South Sudan focused on leveraging the electric potential of the White Nile, going as far back as 2011. To this day, no hydroelectric project has been fully completed in South Sudan.

In my paper, I then point out how this line of thinking can be applied to water purification systems, specifically UV LEDs. Unlike taste-altering chlorine tablets or expensive reverse osmosis systems, small LED systems can be installed economically and independently in conjunction with decentralized power systems to provide clean tasting water. And although there are still some cost issues, these systems are good enough to be used at critical points of infrastructures like hospitals.

Herbert, F. (2006). Dune. Hodder Paperback.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. 1st. ed. New York, Knopf.

Hopefully nobody spent too much time looking at the photo I made for this particular entry. It's a bit embarrassing, but I have little doubt that Star Trek has been, and shall always be, my favorite television show to watch. There are so many things to enjoy about the vast variety of stories told in the franchise. I've read that people enjoy the professional porn. Others like the exploration and science aspects. There are also the cool technologies and the various aliens of the week.

Whenever I see documentaries about Star Trek, however, it felt as though the producers and editors always take the "look how Star Trek inspired this astronaut, this engineer, or this doctor" approach. It's cool I must admit. When Samantha Cristoforetti put on her Captain Janeway outfit while on the ISS, I completely fanboyed out for sure. Then she made an espresso! In space!

But I think it is undersold just how the universe of Star Trek can be inspiring to those of us outside of the overachievers club. What I love most about Star Trek is how it portrays an optimistic possibility of the future of humanity, our humanity. It's not supposed to be some alternate dimension. Its future San Francisco was once our own San Francisco. In our possible future, we celebrate and defend each other's differences and rights, we solve most conflicts with clear communication, and we always seek to improve ourselves in pursuit of personal truth.

Sure, that type of future benefits from post-scarcity technology. However, the existence of the Federation's foils, such as The Dominion or The Romulan Empire, demonstrates that simply having the technology does not mean everyone's needs are met and then some. The Citizens of the Federation in Star Trek still chose their institutions, including the more socialistic ones like the removal of currency.

Now compare that future to the possibility presented in Frank Herbert's Dune. In that possibility, our future humanity chose to renew institutions like feudalism and slavery. It's a universe in which life is cheap and even the fortunate still find themselves at the mercy of benevolent masters. Despite the cool futuristic technologies, is that future really a developed one? An improvement over what we have today?

Back on planet Earth today, I've noticed that many of the people I try to learn from have their own personal shades of what development means to them, in addition to more common interpretations like consumption rates. Professor Ram told me the first day of class that our work focuses on the alleviation of human suffering for future generations. Measurements like infant mortality or illiteracy can represent the worst pains a person can experience. In the late nineties, Amartya Sen challenged us to view development as measured by levels of freedom. The more free a society is, the more developed it is and the more it has the means to develop.

I think I want my personal interpretation of development to include the future that Star Trek represents. That being said, I'm still gonna gently ridicule some of the rough spots... cough... cough... Discovery. Good messaging doesn't excuse frustrating and potentially harmful writing.

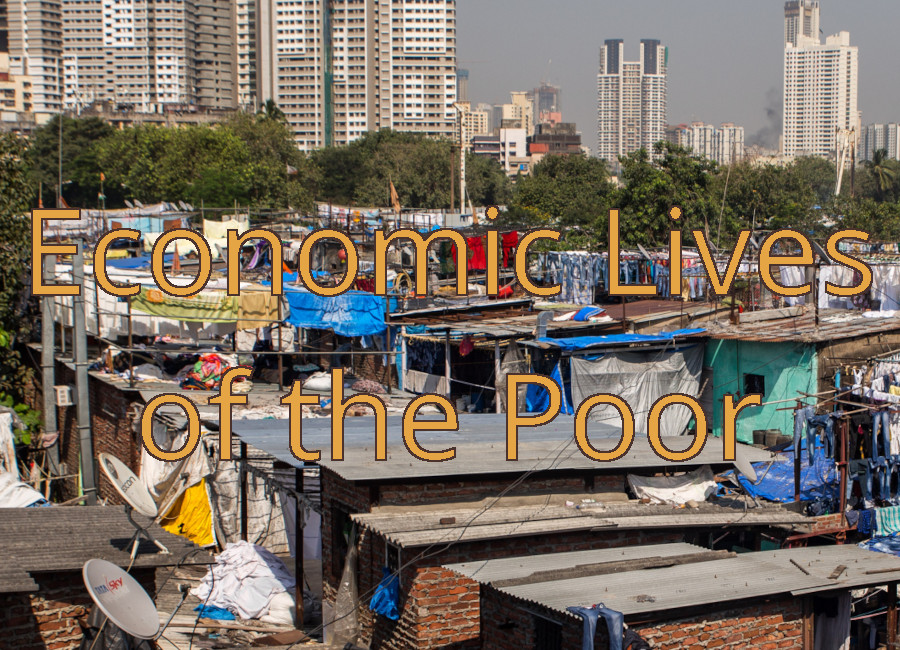

Banerjee, Abhijit, V., and Esther Duflo. 2007. "The Economic Lives of the Poor." Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21 (1): 141–168.

I first read this essay in Professor Hartman's International Development class. It is a great read for anyone, especially because it contains little math or statistics. Instead, the authors use a descriptive tone to illustrate the day-to-day challenges faced by the poor.

I think that what stands out the most to me about this paper is the humanity felt within the tone. It can be very easy to turn economic work into something dry or sterile, even if it is about the world's poorest. The authors remind us that these are still human beings who expend income on things like radios, televisions, weddings, and other social ceremonies.

It is super easy to say that the poor could be "better stewards" with their limited income, that they can consume food with better calorie/cost ratios, or that they can cut off all "extraneous" spending. But those types of measures shouldn't be an option. We who want to work this field need to recognize that. In short, there is no shame in the poor trying to live like a human beings because they are human beings.

Another thing that also interests me about this paper is the placement of entrepreneurial spirit in a negative light. Many of the poor enter into businesses for themselves, such as selling bread or sewing clothing. But as the authors point out, there are too many people stuck doing these activities and not specializing. I just find it funny. Having lived in The Bay Area, plus having studied in Israel, it has always been impressed upon me that such risk-taking endeavors in the pursuit of lucky profit is something to be admired. Guess context matters quite a bit.